Golden Is Good… But So Are White and Pale Yellow Spores—Here’s the Science

A Story from the Farm That Opened Everyone’s Eyes

A farmer once visited our field demo carrying two samples of mycorrhiza spores.

One had golden-yellow spores—bright, shiny, and visually impressive.

The other had white and pale-yellow spores—simple, dull, easy to underestimate under microscopy.

He asked:

“Saheb, aa banema thi kayu sachu kaam karse? (Which one will work better?)”

Almost everyone pointed to the golden spores.

But the soil told a different story!

When we tested both samples:

- Some golden spores did not stain in the MTT assay → meaning they were dormant or old

- The white and pale-yellow spores turned deep blue hue→ showing strong viability and active metabolism

- Pale spores colonized roots more quickly

- Field plots with pale spores showed better early growth and stronger root networks

The farmer was surprised.

But this is exactly what the science says: Golden spores are good—but white and pale-yellow spores are equally good, often even more active.

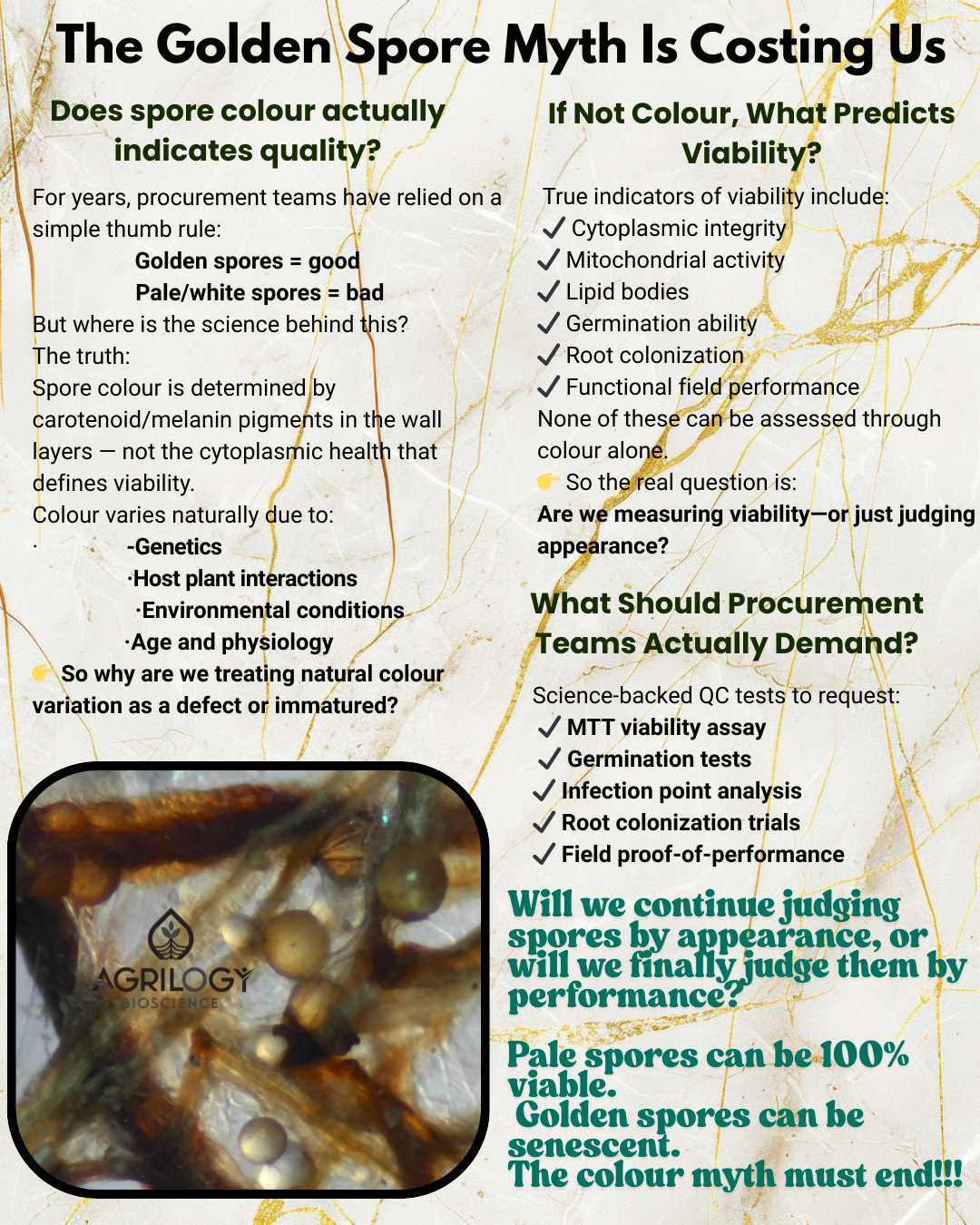

Why Colour Alone Misleads Us

A mycorrhiza spore’s colour—whether white, pale yellow, cream, or golden—naturally varies due to its genetics, the host plant it grew with, the soil and environment it developed in, its age, and the carotenoid pigments in its outer wall. Because these factors influence only the outer appearance, colour alone cannot indicate a spore’s internal health or viability. Just like wheat grains that differ slightly in shade but grow equally well, mycorrhiza spores also show harmless colour variation. The real indicator of quality is not colour, but whether the spore is alive and capable of colonizing roots.

White and Pale-Yellow Spores: Naturally Efficient Contributors to Soil Health

White and pale-yellow AMF spores are not weak or immature—multiple authoritative sources, including INVAM (International Culture Collection of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi) and GINCO-BEL (Belgian Glomeromycota Collection), document that many well-known, highly functional AMF species naturally produce spores in lighter shades. These pale-coloured spores belong to species that play a strong role in nutrient mobilization, hyphal spread, soil aggregation, and root colonization, often performing as effectively as darker or golden spores. AMF reference databases also show clear evidence that pale-coloured spores are common in Glomeraceae and other agriculturally important families, where colour variation is considered a normal taxonomic trait, not a sign of poor quality.

Because of this natural diversity (Polymorphism), pale and white spores consistently contribute to soil ecology by improving phosphorus and micronutrient uptake, enhancing water-use efficiency, increasing soil microbial activity, and supporting carbon storage through extensive hyphal networks.

Thus, the presence of white or pale spores in a product is fully aligned with natural AMF biology and reflects the diversity found in verified, curated AMF collections worldwide.

Myth vs. Reality: Colour Does Not Indicate Viability

It is a common belief that yellow or golden spores are always viable and white or pale spores are non-viable, but MTT assays and global AMF references show this is not true. Golden spores often fail to stain in MTT because they may be senescent, dormant, or pigmented in a way that limits dye penetration, meaning their colour alone cannot confirm activity or viability. In contrast, white and pale-yellow spores frequently stain deep blue, indicating active metabolism, healthy cytoplasm, and readiness to germinate.

So the reality is clear:

Yellow spores are not automatically viable, and white/pale spores are not automatically non-viable. Viability depends on the internal physiology of the spore, not its colour.

What Actually Determines Spore Quality?

Real quality depends on:

- Germination ability

- Cytoplasmic health

- MTT viability

- Hyphal growth

- Root colonization %

- Infection points

- Field performance

Not on colour.

Colour only tells appearance—not power.

Appearance Isn’t Quality: Rethinking AMF Procurement Standards

For procurement teams, judging spore quality by colour alone may seem simple, but it causes significant hidden losses. When white or pale-yellow spores are rejected purely because they don’t “look” ideal, procurement unknowingly discards many viable, high-performing spores that global AMF collections such as INVAM and GINCO-BEL consider completely natural. This leads to avoidable batch rejections, reduced usable output, higher production costs, and inconsistent final product quality.

Colour-based filtering also increases the risk of supplying farmers with visually appealing—but biologically weaker—products. By removing pale spores that often show strong metabolic activity in tests like MTT, procurement unintentionally reduces the overall viability of the formulation. This undermines field performance and long-term trust in the brand.

Moreover, rejecting pale spores deprives the soil of beneficial fungi that contribute to nutrient uptake, root development, and soil structure. These losses highlight why global AMF experts do not use colour as a quality parameter. Procurement accuracy improves dramatically when decisions are based on functional viability, germination, and colonization ability, rather than superficial appearance.

What Should Be Practical Action Check List?

1. Update Procurement SOPs

Adopt the natural colour range of AMF spores — white, cream, pale yellow, and light golden — as acceptable and normal variations.

2. Train QC & Field Teams

Clarify that lighter spores are not weak; they are natural and often show higher metabolic activity in viability tests.

3. Educate Farmers in Simple Terms

Use farmer-friendly explanations such as:

“Spore nu rang quality nathi batavtu; MTT ma neelo rang jivant spore batave chhe.”

4. Follow Science-Based Quality Checks

Rely on MTT viability, germination, and colonization efficiency, rather than colour-based selection.

5. Promote Soil-Health–First Communication

Show how pale spores improve nutrient uptake, root strength, and long-term soil fertility year after year.

Spore Colour Is Just Nature; Viability Is the Truth

Golden spores are good.

White spores are good.

Pale-yellow spores are good.

Every colour is simply a part of nature’s diversity—and all can support strong roots, healthy soil, and better crops. What truly matters is viability, not appearance.

It’s time to move beyond colour myths and build a future driven by science, soil health, and honest quality standards that deliver real value to farmers.

Because ultimately…

Crops don’t grow from the colour of the spore—they grow from the life and activity within it.

The Complexity Behind MTT Staining: Navigating Variability in Spore Viability Testing

When it comes to assess the viability of fungal spores (especially VAM Fungi), the MTT assay seems like a simple solution—just add the dye and observe the colour change. But what happens when the colour reactions are anything but straightforward? Dive into the controversies and complexities behind MTT staining and discover why accurate interpretation of spore viability is trickier than it seems.

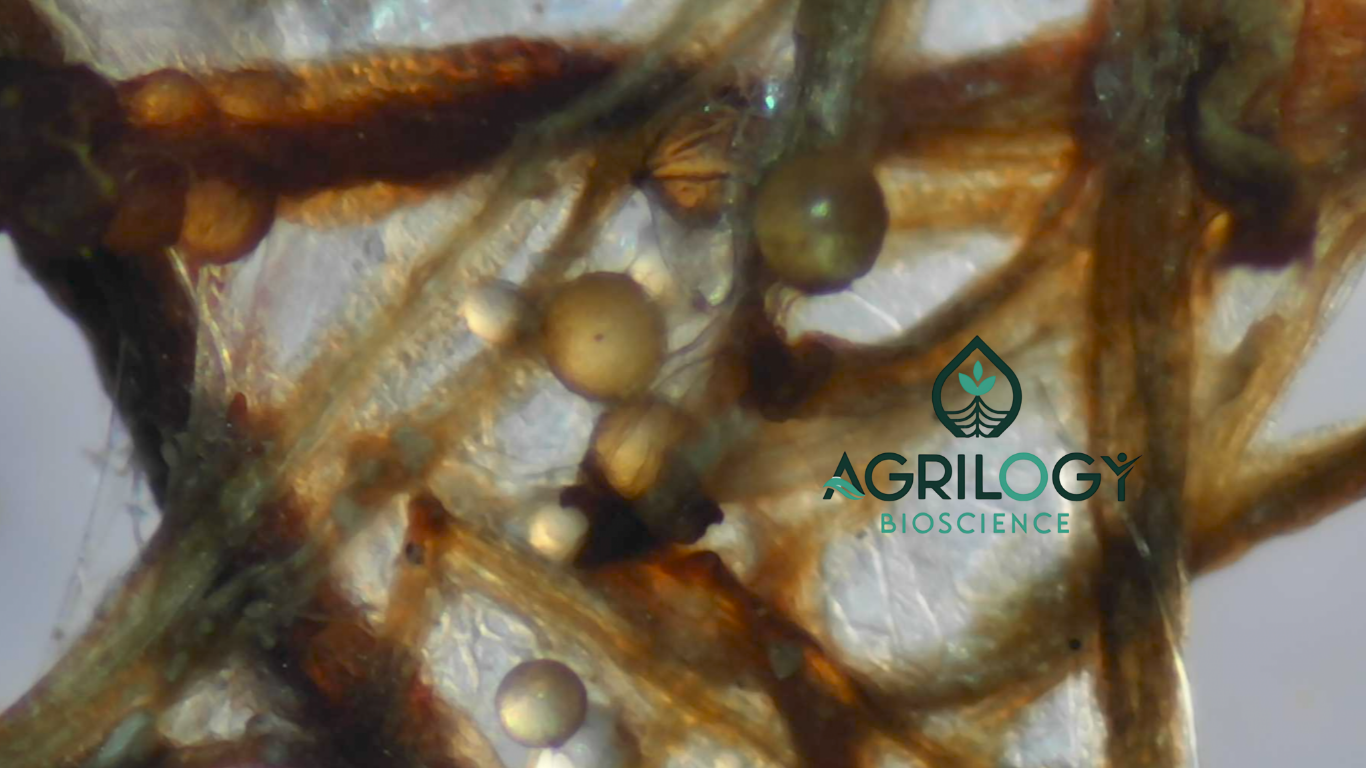

Assessing the viability of fungal spores, particularly those from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF or VAM), is essential for understanding their role in plant symbiosis.

One widely used method for evaluating spore viability is the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. This assay measures the metabolic activity of spores, offering a visually accessible indicator of their health. However, despite its popularity, MTT staining can lead to inconsistent and sometimes controversial interpretations. Let’s break down the principles behind MTT, its colour interpretations, and the factors that cause variability in results.

What is MTT Dye?

MTT is a yellow tetrazolium dye that is reduced by cellular dehydrogenases, enzymes that play a critical role in cellular respiration. When the dye is reduced in respiring cells, it forms a purple formazan product. The intensity of the purple colour directly correlates with the metabolic activity of the cells or spores, making MTT a useful tool for assessing cell viability. For VAM spores, this process indicates whether the spores are metabolically active and potentially viable for symbiosis with plant roots.

How Does MTT Work?

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) staining is a widely used assay to assess cell viability based on metabolic activity. When introduced to living AMF or VAM cells, MTT is reduced by mitochondrial dehydrogenase enzymes, which disrupt the tetrazolium ring structure and form a purple-coloured formazan product. This reaction occurs in metabolically active cells where enzymes, aided by cofactors like NADH or NADPH, facilitate the reduction process.

The resulting formazan accumulates inside the cytoplasm, and the intensity of the colour produced correlates directly with the cellular metabolic activity of the spore. The ease with which MTT passes through the lipid membranes of viable cells ensures its effective uptake, making it an excellent indicator of cell health and viability. The amount of formazan formed is a quantitative measure, offering a reliable insight into the viability of cells or spores, such as VAM spores, by highlighting their metabolic capacity.

MTT Assay Protocol for Spore Viability Assessment:

The MTT Assay Protocol involves weighing 1 gram of the sample (e.g., fungal spores) and washing it under tap water multiple times. The collected spores are diluted in freshly prepared 0.25% MTT dye. The mixture is then inverted to ensure thorough mixing and incubated at 27°C in the dark for 24, 48, and 72 hours. After incubation, the sample is washed 3-4 times with tap water and then suspended in 10 ml of RO water. A 0.5 ml aliquot is placed on a petri dish and examined under a stereo zoom microscope for spore viability.

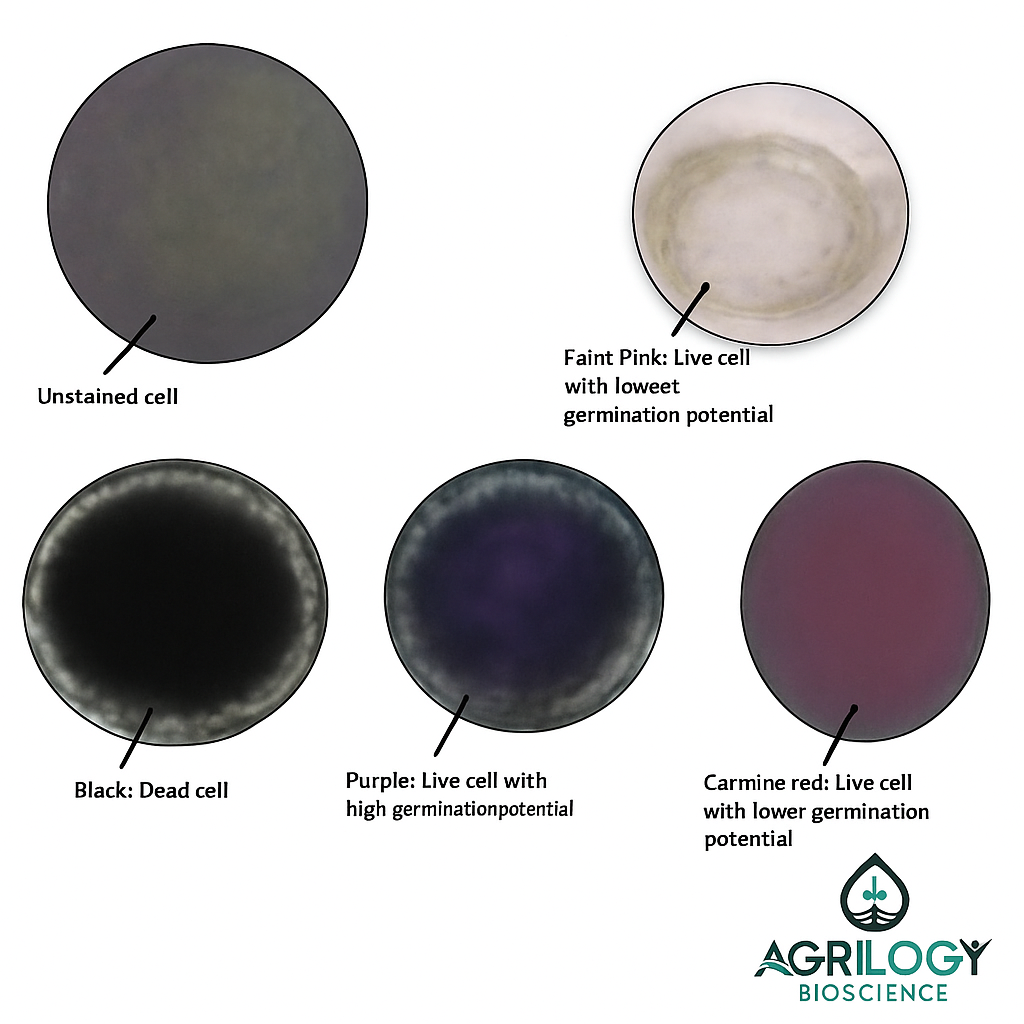

Colour Interpretation and Its Significance:

The colour changes in MTT staining offer critical insights into spore viability. However, these changes are not always straightforward:

- Red/Pink/Purple Spores: Viable spores typically stain red, pink and purple with the intensity of the colour corresponding to the level of metabolic activity. A purple colour indicates active dehydrogenase enzymes, while a pink hue suggests lower metabolic activity.

- Black Spores: Black spores are often assumed to be non-viable, as they suggest excessive formazan accumulation in the cytoplasm upon reduction by cellular reducing agents. However, black coloration may also result from overstaining, leading to ambiguities in viability interpretation.

- Unstained Spores: Chemically killed or non-metabolically active spores will not reduce MTT, and thus remain yellow, indicating non-viability.

Despite these general rules, variability in results often complicates the interpretation of spore viability.

Controversies and Sources of Variability in MTT Staining:

Although MTT staining is widely used, its application comes with notable challenges. Here are some key factors that contribute to its variability:

1. Overstaining and Misleading Black Spores:

✓Black coloration in MTT staining is commonly linked to non-viability, but this can be misleading. Excessive MTT accumulation or prolonged incubation can result in black spores, even if they are still viable. Therefore, black coloration should not be automatically interpreted as a sign of non-viability.

2. Impact of Spore Age and Wall Thickness:

✓Older spores, particularly those that have been stored for extended periods, require higher concentrations of MTT or longer incubation times to reach a maximum colour change. Furthermore, the thickness of the spore wall can affect the penetration of MTT. Thicker walls may limit the dye’s access to the enzymatic sites, resulting in inconsistent staining and variability in colour reaction.

3. Dormant Spores and Metabolic Decline:

✓Spores stored for long periods often experience a decline in metabolic activity. These dormant spores may still reduce MTT, producing faint red or pink hues despite being non-viable in terms of germination or colonization. This presents a challenge in distinguishing between dormant and truly viable spores, as they may still display metabolic activity despite not being capable of establishing symbiosis.

4. Chemical Reducing Agents in Non-Viable Spores:

✓Non-viable spores may still reduce MTT due to the presence of reducing agents like cysteine, sulphur-containing compounds, or reducing sugars. These chemicals can catalyse the reduction of MTT even in the absence of active dehydrogenase enzymes, leading to false positives and incorrect conclusions about spore viability.

5. Species-Specific Variability:

✓Different VAM species exhibit varying metabolic activity levels. As a result, their responses to MTT can differ significantly. Some species may require longer incubation or higher concentrations of MTT to achieve a visible colour change, making standardization across species challenging.

6. Difficulties in Interpreting Pink Spores:

✓Pink spores can be particularly problematic. A faint pink colour may suggest minimal metabolic activity, but it is difficult to determine whether the spores are dormant or in a state of partial viability. These spores may be capable of reducing MTT but lack the resources to germinate or colonize plant roots.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of MTT Staining:

While MTT staining is a useful and widely employed technique for assessing the viability of fungal spores, it is far from perfect. A thorough understanding of its limitations is essential for accurate interpretation. Factors such as overstaining, spore wall thickness, spore age, and the presence of reducing agents must be carefully considered when analysing the results. In particular, the ambiguous interpretation of black or pink spores underscores the need for caution in drawing conclusions based solely on MTT staining.

To minimize variability and ensure reliable results, optimization of experimental conditions is essential. Researchers must account for species-specific characteristics, spore age, and other confounding factors in order to achieve accurate assessments of fungal spore viability. In summary, MTT staining is a valuable tool, but its complexity requires a refined approach for obtaining meaningful data.

Key Takeaways:

- MTT staining helps assess spore viability by measuring metabolic activity through colour changes.

- Red or pink colouration typically indicates viable, respiring spores, while black colouration can indicate overstaining or non-viability.

- Factors like spore age, wall thickness, and the presence of reducing agents can affect MTT staining results, leading to potential misinterpretations.

- Optimization of experimental conditions is crucial for accurate viability assessment across different VAM species.