How to Make Biologicals Work? Optimizing the Soil-Root-Microbe System!

The promise of agricultural biologicals—from nitrogen-fixing bacteria to mycorrhizae fungi—is transforming modern farming. However, their success is not guaranteed by application alone. Unlike chemical inputs, these living products are sensitive performers in the complex realm of the soil and rhizosphere. Their efficacy depends on a symphony of environmental factors working in harmony. Here, we break down the core scientific parameters and management strategies that determine whether your biological investment will flourish or falter.

The Foundational Trio: pH, Redox Potential and Temperature

Think of these as the non-negotiable core abiotic driversfor your microbial workforce.

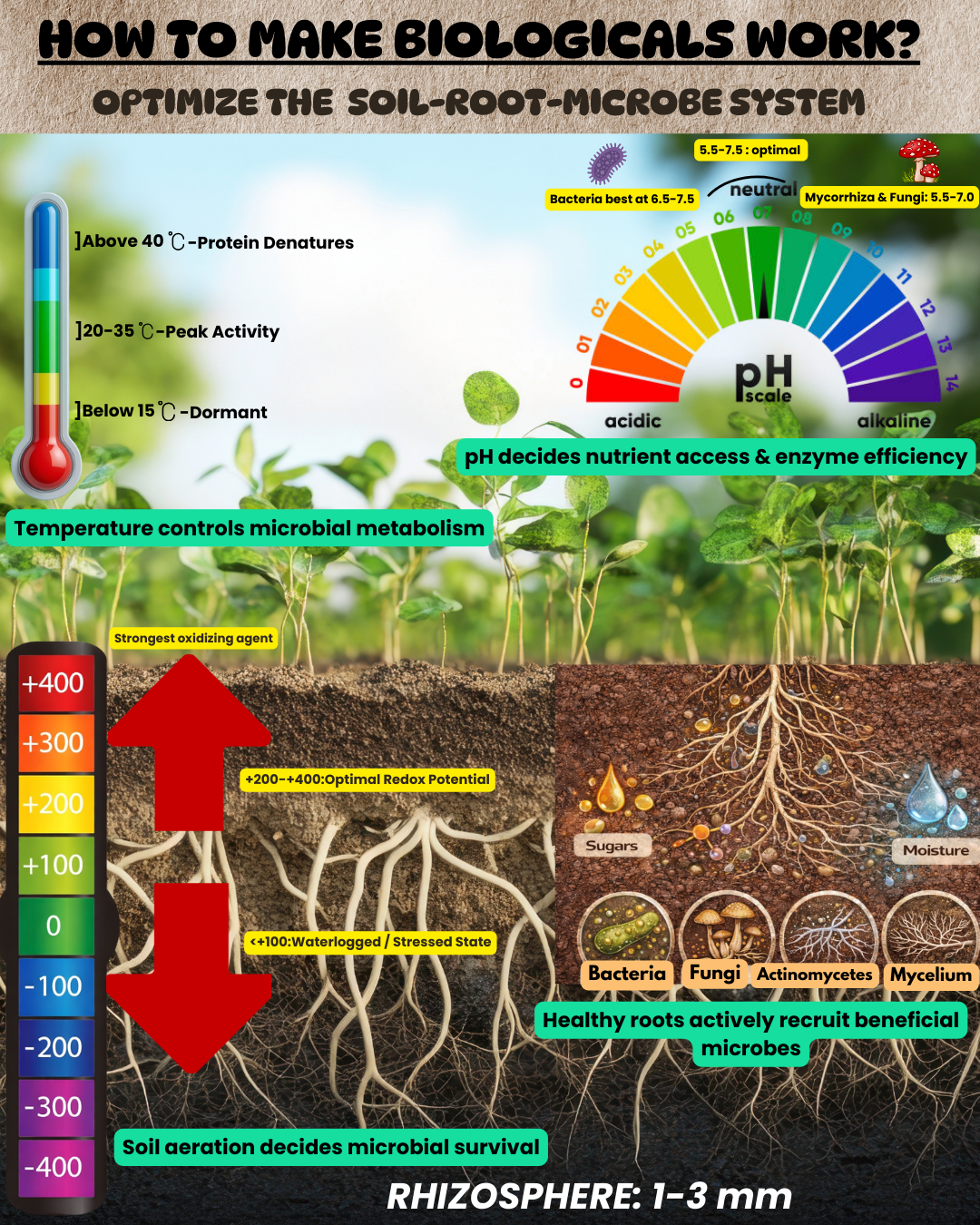

A. Redox Potential (Eh): The Breath of the Soil

Redox potential measures soil aeration, essentially telling you if your soil is gasping for air or breathing easily.

- Physiological Optimum: +200 to +400 mV for most beneficial aerobes.

- Microbial Preferences: Nitrogen-fixing Rhizobium needs well-aerated soil (Eh > +300 mV) to form nodules. PSB Pseudomonas operates well at moderate levels (+100 to +300 mV). Notably, while some anaerobes function at negative Eh, they are less common in standard biologicals.

- Key Insight: A waterlogged, low-Eh (< +100 mV) environment will suffocate many aerobic Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR), though it may be less detrimental to certain fungi.

B. pH: The Acidity Balance

pH dictates nutrient availability and microbial membrane stability.

- Bacterial Preference: Thrive in neutral to slightly alkaline soils (pH 6.5-7.5), with exceptions like acid-tolerant strains.

- Fungal Preference: Enjoy a broader, slightly more acidic range (pH 5.5-7.5), with mycorrhizae performing optimally at pH 5.5-7.0.

- Critical Impact: pH directly influences enzyme activity and the efficiency of siderophores—the iron-scavenging molecules produced by many biocontrol agents.

C. Temperature: The Metabolic Thermostat

Temperature controls microbial activity and protein integrity.

- Optimal Range: 20-35°C (mesophilic range) for most products.

- Critical Thresholds: Activity significantly slows below 15°C, while sustained heat above 40°C can denature proteins in many PGPRs.

- Strategy: Match the inoculant to the season. Seek out psychrotolerant strains for early spring or fall applications and thermotolerant strains for summer use.

The Plant's Role: Root Architecture is Everything

The plant is not a passive recipient but an active regulator of its rhizosphere microbiome through its root architechture.

- Root Surface Area: Finer root systems create more sites for colonization.

- Root Exudates: This is the plant's chemical communication. Legumes secrete flavonoids to attract Rhizobium, while cereals release malic acid to beckon Bacillus subtilis. The quantity and quality of these exudates drive microbial chemotaxis.

- Root Hair Density: This is often the frontline for bacterial colonization—higher density means more entry points.

- Root Depth: Shallow root systems favour mycorrhiza partnerships, while deeper roots may require strategically placed inoculants.

Building a Favourable Soil Ecosystem

Beyond the core trio, a thriving soil ecosystem sets the stage for success.

A. Physical & Chemical Properties:

- Aim for loamy soils with good porosity (40-60% pore space) to allow microbial movement.

- Maintain organic matter above 2% to provide carbon and buffer changes.

- A C:N ratio of 20:1 to 30:1 is optimal. Avoid excessive nitrogen or phosphorus, which can inhibit biological N-fixation and P-solubilization.

- Ensure low salinity (EC < 2 dS/m) and a Cation Exchange Capacity > 10 cmol⁺/kg for nutrient retention.

B. The Rhizosphere Hotspot:

This 1-3 mm zone around the root is the action centre. Manage for:

- Exudate Profiles: A mix of sugars (energy), amino acids (nitrogen), and organic acids (chelation).

- Mucilage Production: Creates a protective "rhizo sheath" for microbes.

- Moisture: Ideal at 60-80% of water holding capacity.

Synergies and Strategic Application

Understanding how different inoculants interact with their environment allows for smarter combinations.

- Bacterial inoculants perform best in well-aerated soils with a redox potential of +250 to +400 mV, moderate temperatures between 25–32°C, and plant roots that have a high density of root hairs, which provide more attachment sites for bacteria.

- Fungal inoculants, including mycorrhiza, prefer slightly lower redox conditions of +200 to +350 mV, cooler temperature ranges of 20–28°C, and plants with extensive lateral root systems, as these roots enhance fungal colonization and symbiotic spread.

- Actinomycetes thrive under highly aerobic conditions with a redox potential of +300 to +450 mV, warmer temperatures of 28–35°C, and rhizospheres characterized by moderate to high root exudation, which supplies the organic compounds they require for sustained activity.

A Practical Optimization Protocol:

- Pre-Application: Assess soil health cards, root health, and native microbial load.

- Application Timing: Apply when soil temperature is >15°C, during active root growth, to moist (not saturated) soil, ideally in early morning or late evening to reduce UV damage.

- Post-Application: Monitor rhizosphere colonization, plant vigour, and soil respiration rates.

The Key Takeaway

Successful biological application is an exercise in system optimization, not a single-factor fix. It requires managing the rhizosphere as a holistic ecosystem where soil physics, chemistry, and biology converge to support plant-microbe performances. The most effective strategy combines regular, detailed soil testing with keen root health assessments, creating a feedback loop for continuous improvement. By tuning the stage—the soil environment—you enable the living actors in your biological products to deliver their full, transformative performance for your crops.