The Clustered Code: Deciphering the Secret Life of Mycorrhizal Spores

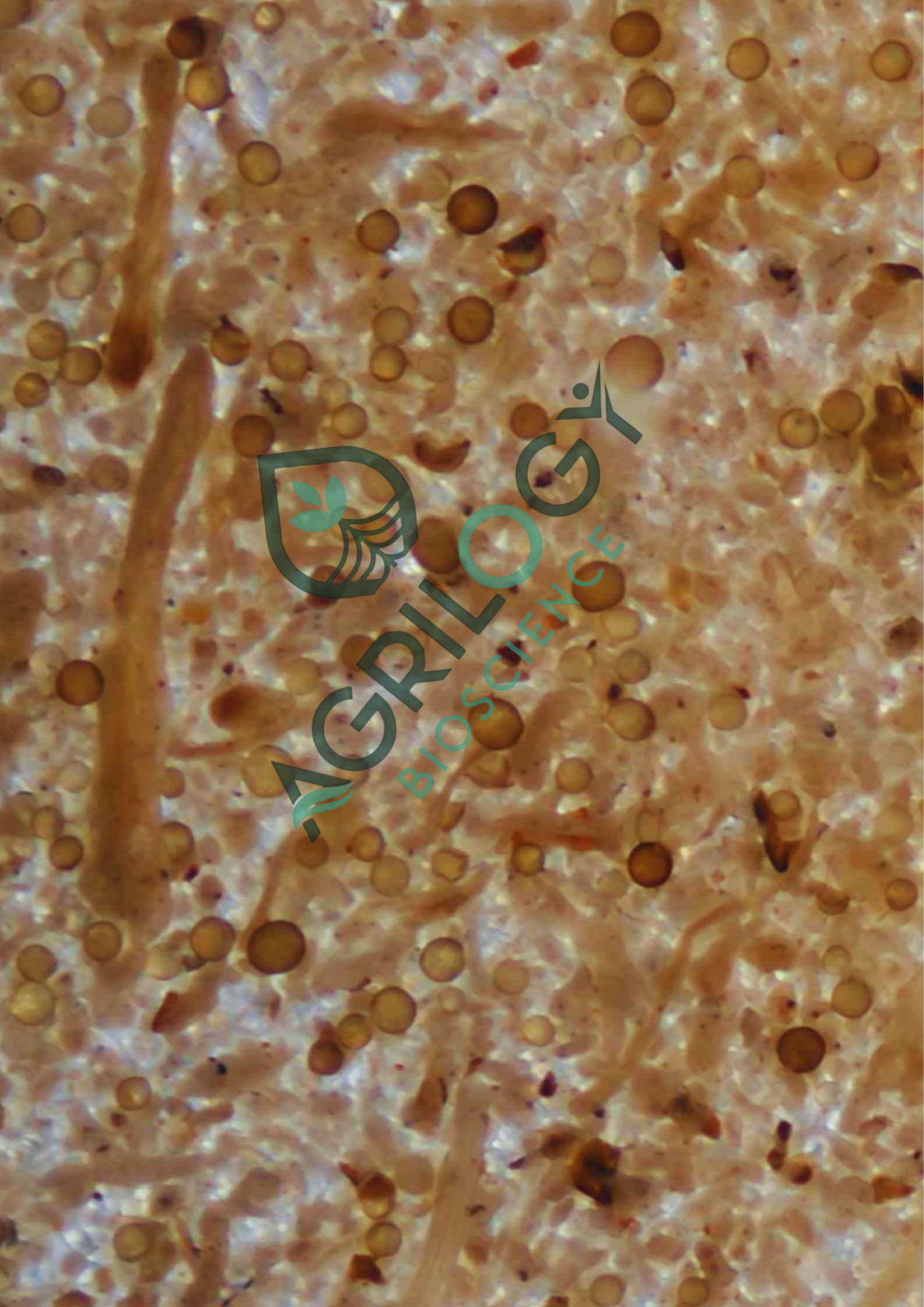

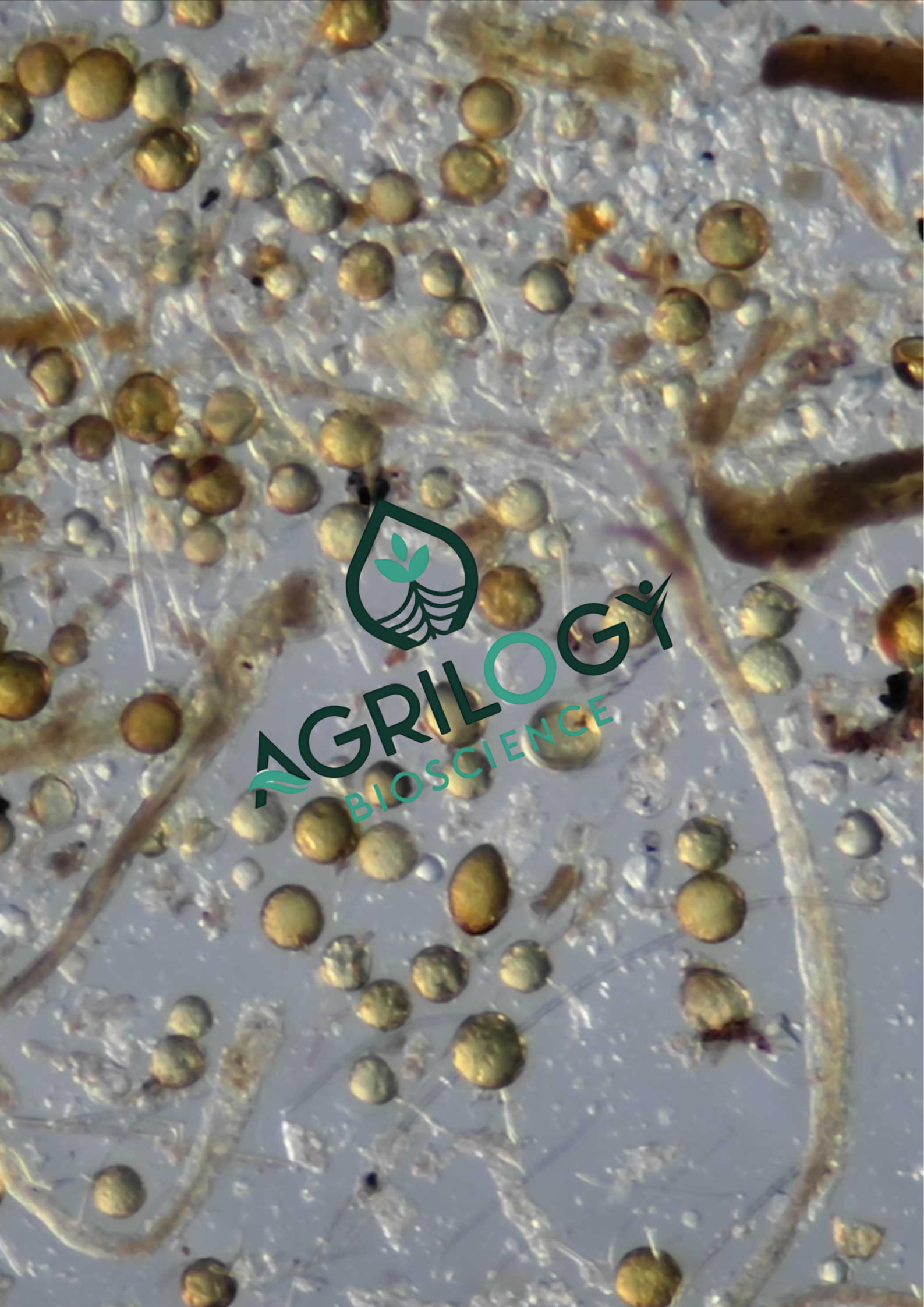

If you’ve ever peeked through a microscope at arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi spores, you’ve likely seen them: not just solitary spheres, but intriguing clusters where spores appear glued together like microscopic bunches of grapes. For years, these aggregated spores—particularly of the ubiquitous species Glomus intraradices (now classified within the Rhizophagus genus)—were often counted as one unit or overlooked. But emerging science reveals that this "clustering" is not a random accident. It's a sophisticated survival strategy with profound ecological implications. Let's dive into the sticky, clever world of clustered endomycorrhizal spores.

The Microscopic Glue: How Spores Stick Together?

First, the mechanics. How are these spores so firmly aggregated?

The binding agent is a complex matrix of extraradical mycelial networks and glycoprotein-based secretions. Think of it not as a simple adhesive, but as a living, “biological hydrogel”.

- The Hyphal "Backbone": Often, spores are formed at the tips or along the length of the extraradical hyphae (the fungal network outside the plant root). Instead of detaching, the hyphae connecting them thicken, melanize, and persist, forming a durable structural scaffold that physically links the spores.

- The Secreted "Bio-Glue": As spores mature, they and their supporting hyphae exude a cocktail of glycoproteins, mucilaginous polysaccharides, and hydrophobins. This secretion hardens upon dehydration, forming a tough, protective crust that cements the entire assembly—spores, hyphae, and soil particles—into a single, cohesive unit. This crust is key to the cluster's resilience.

Why Cluster? The Ecological & Physiological Genius of Glomus intraradices

For Glomus intraradices, a champion of crop and grassland systems, spore clustering is a masterclass in evolutionary adaptation.

1. The Ecological - Propagule Bank Microsite:

- Desiccation Defence: The shared, hardened glycoprotein matrix significantly reduces the surface area exposed to the environment, minimizing water loss. It creates a buffered microclimate around the spores, protecting them from drought.

- Predator & Pathogen Deterrence: The same tough, often melanised crust that prevents water loss also acts as a physical barrier against grazing by soil micro arthropods and invasion by parasitic fungi. It's the spore's version of a castle wall.

- Nutrient Reservoir & Hub: A cluster isn't just spores; it's a package of stored carbon, lipids, and nutrients. This shared "communal pantry" may allow for resource redistribution, potentially aiding weaker spores within the unit. The interconnected hyphae can also function as a pre-established network, giving new germination an instant head start.

2. The Physiological Powerhouse:

- Synergistic Germination Signals: There is compelling evidence that spores in a cluster can engage in cross-talk. A spore initiating germination may release chemical signals (e.g., strigolactones in response to root exudates) that can stimulate or prime neighbouring spores in the cluster, leading to coordinated, potentially more effective colonization events.

- Adaptive Diversification (of Dormancy): Not all spores in a cluster germinate simultaneously. This asynchronous germination is a critical risk-management strategy. If one spore germinates into unfavorable conditions and fails, others remain dormant, preserving the genetic lineage. It ensures the fungus doesn't put all its eggs in one basket.

The Germination Paradox: Does Clustering Help or Hinder?

This is the central question. The answer is nuanced: clustering delays but optimizes germination.

- The Delay: The physical barrier of the crust and the need to re-hydrate a larger, denser structure mean that clustered spores often germinate more slowly than solitary spores. They require a stronger, more persistent stimulus (like continuous root exudates) to initiate the process.

- The Ultimate Advantage: This delay is strategic. It acts as a dormancy filter, ensuring germination only occurs when conditions are truly favourable and a host root is reliably nearby. When they do germinate, they benefit from the "synergistic signals" and pre-built hyphal connections, potentially leading to more robust and successful colonization. The cluster ensures quality over speed.

A Call to Action: Why Specialists MUST Reconsider Spore Counting

This brings us to a critical methodological point. For mycorrhizal ecologists, agronomists, and inoculum producers, treating a spore cluster as "one" is a significant error. Here’s why:

- Inaccurate Propagule Potential: A cluster of 10 spores has 10x the genetic potential and nutrient reserves of a single spore. Counting it as one propagule drastically underestimates the true infectious potential of the soil or inoculum.

- Skewed Biodiversity & Abundance Data: In ecological surveys, failing to dis-aggregate clusters lead to severe underestimation of spore density and can distort comparisons between species (some cluster more than others) or between management practices.

- Misjudging Inoculum Quality: The proportion of clustered vs. solitary spores in a commercial inoculum could be a key quality indicator. A high cluster ratio suggests a product designed for resilience and long-term survival, while a high solitary spore count might indicate faster, but less persistent, colonization.

Best Practice: The specialist's approach should involve gentle crushing of samples in a weak surfactant solution to break up clusters before counting, providing a true measure of total spore numbers. Documenting the degree of clustering separately adds a valuable layer of ecological insight.

“Taken together, the physical structure, biochemical signals, and germination patterns indicate that the spore cluster functions as a unified survival module.".

Clustering represent a shift in how we view these fungi—not as collections of individual spores, but as complex, cooperative societies engineered for persistence.

Their sticky glue is the mortar of a survival fortress, their delayed germination a mark of wisdom, and their continued underestimation in counts a gap in our understanding.

By acknowledging and studying these clustered formations in their full complexity, we unlock a deeper appreciation of mycorrhizal ecology and move closer to harnessing their full power for sustainable agriculture and ecosystem restoration.

“Look closer. Count smarter. The future of soil health depends on such microscopic details.”